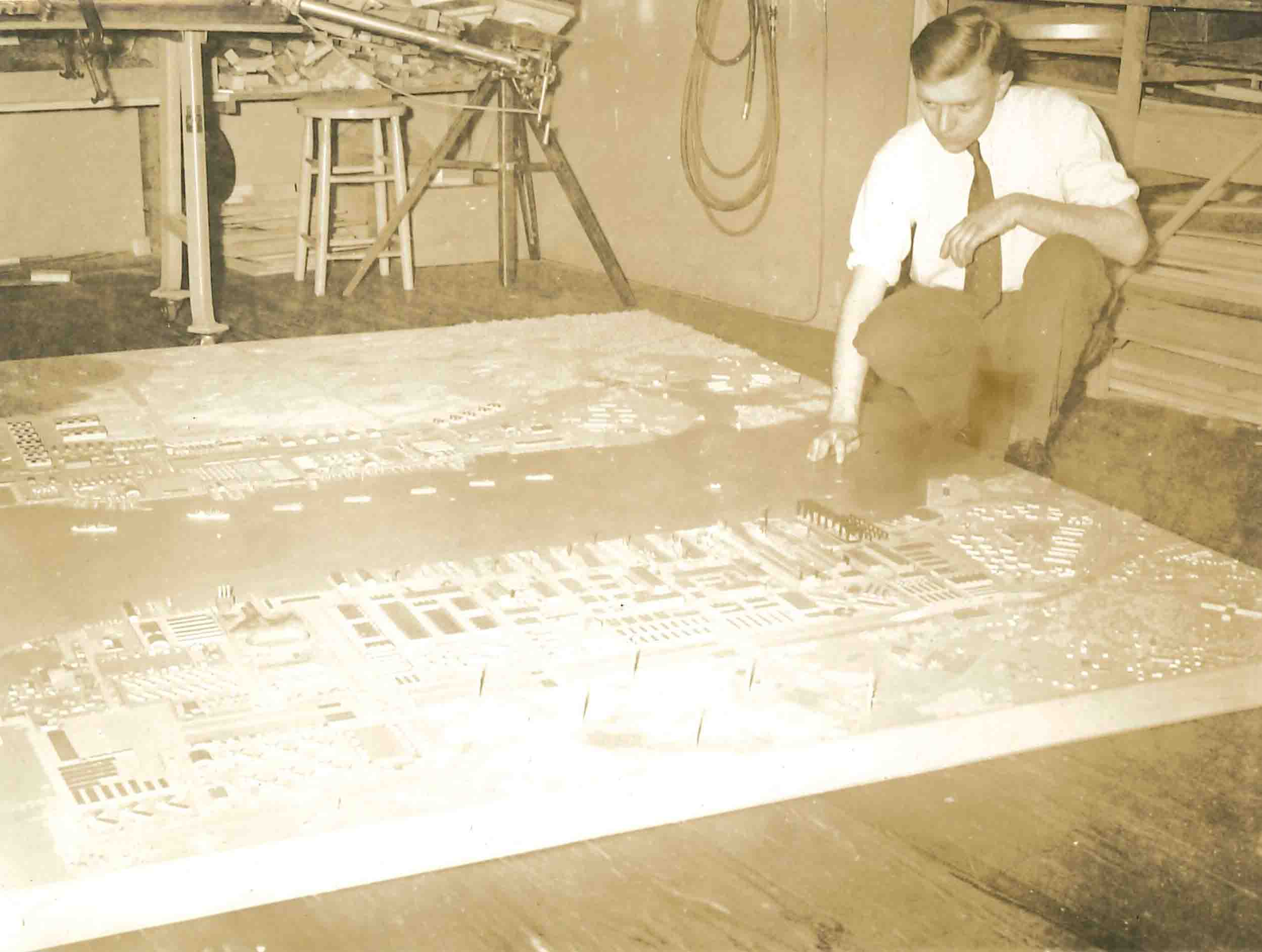

“Ted Conrad has probably built more New York real estate than anyone else—in miniature, that is.”

Upcoming events

Online lecture: Of Models and Men. Theodore Conrad, Louis Checkman and the Miniature Boom in New York”

[response: Matthew C. Hunter]

Princeton University Media + Modernity Program, November 9, 2021, 5 p.m. ET

online lecture: The Architectural Models of Theodore Conrad

Skyscraper Museum, New York City, December 7, 2021, 6 p.m. ET

Online Lecture: Plexiglas und Kameras. Theodore Conrad, Louis Checkman und der New yorker Architekturmodellboom 1950-1970

CCSA Center for Critical Studies in Architecture, January 20, 2022, 6 p.m. CET

Online Lecture: Theodore Conrad and the Miniature Boom

Theodore Conrad is probably the first and so far only model maker to whom the New York Times has dedicated an obituary. Teresa Fankhänel was able to open the cabinet of curiosities in his workshop in New Jersey in its original state. Louis Checkman's photo studio was in the immediate vicinity. A cross-media partnership emerged from the interaction and is presented for the first time in the book "The Architectural Models of Theodore Conrad. The "miniature boom" of mid-century modernism.

Association of Professional Model Makers, February 2, 1 p.m. EST

The story behind the book

The architectural models of Theodore Conrad

In 1949, the young architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill presented the board of directors with their final design for Lever Brothers’ new headquarters in New York. They did so with the help of a newly developed model that was, according to those present, not just "small but spectacular." The model convinced the board to erect a completely unprecedented building with a glass curtain wall that would soon be copied around the world. A few years later, right across from Lever House on Park Avenue, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Seagram Building was already under construction when a gigantic four-meter-tall miniature was set up outside the hoarding of the construction site, presenting yet another glimpse of the future.

The two spectacular models of two of the most innovative and modern buildings of their time were the work of the same man. Their maker, Theodore Conrad of Jersey City, was America's most prominent and successful architectural model maker during the years following World War II. With his oeuvre, he not only revolutionized the production of models through the use of new materials and modeling techniques but became one of the first entrepreneurs to specialize solely in architectural modeling. Yet, despite his success and the well-known buildings he helped to create, little has been known about his own work and legacy—until now, that is.

Research project

It began with a postcard. While I was working as a curatorial assistant at the German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, on the exhibition “The Architectural Model—Tool, Fetish, Small Utopia” which opened in 2012, I was researching a model of Lever House which we wanted to include in the show. As with many models, there wasn’t much information to go on beyond what was documented in the files of the Museum of Modern Art: the name of its maker, Theodore Conrad. Conrad had passed away in 1994 but I was able to locate family members who still lived in his home town Jersey City. While I could not reach anyone in New Jersey I did receive an unexpected call from Offenbach, a suburb of Frankfurt. A cousin of Conrad’s wife happened to live not far from my office and had heard of the postcard I had sent to the U.S. when my attempts at contacting his relatives had failed. The cousin and his wife came to visit me and brought with them a binder full of newspaper clippings and photos documenting Conrad’s work in architectural modeling and a phone number in Jersey City.

Based upon this initial encounter and the discovery of the privately held Theodore Conrad Archive, my doctoral dissertation with the title “The Miniature Boom. A History of American Architectural Models in the 20th Century” was prepared as part of the research project “Architectures of Display” at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, and completed in June 2016.

The miniature boom

When the American journalist Jane Jacobs entitled her 1958 report on architectural model making “The Miniature Boom,” she was certainly unaware of the long-lasting impact that it would have on the historiography of architectural models. Applied today as a label for the peak of architectural model making after World War II, the phrase has left the short life expectancy of the pages of the Architectural Forum to enter a more scholarly discourse . In the following decades, Jacobs’ remarks have reverberated numerous times in the work of scholars and journalists alike. The Miniature Boom has become a household name for mid-century architectural models despite the fact that little research has investigated its origins or questioned the validity of Jacobs’ statements altogether.

Her article was a brief overview that summarized the predominant developments in architectural model making in the late 1950s. What she tried to grasp with the term Miniature Boom were three developments: an increased demand for detailed models by architects and clients, the use of new materials in models, and new, mechanized techniques for processing them. Creating these elaborate and expensive models, a growing number of architectural modelers were able to represent and influence the design and presentation of the new International Style architecture that experienced its commercial heyday in the 1950s and 1960s.

“Nelson A. Rockefeller sent visitors to see the view from his window. Doris Duke argued over doorways. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis first saw what President Kennedy’s grave would look like from a Conrad model.”

The dean of models

New York was home to a considerably large number of model makers before and after World War II, among whom Theodore Conrad remains the most prominent. Jane Jacobs was not the first and certainly not the last to write about Conrad, nor was he the only model maker mentioned in her article. Yet, Conrad’s rank as a central figure of the Miniature Boom is unchallenged. Over the course of his professional career and even after his death in 1994, written accounts of his work have been featured in an extraordinary amount of magazines, newspapers and even a few scholarly publications. An outspoken and avid self-publicist, Conrad added to his printed legacy by sending numerous commentaries to the editors of local newspapers. Most importantly, he compiled and duplicated files of newspaper clippings featuring his work and distributed them among friends and family as well as colleagues and historians, thus hoping to preserve his achievements for posterity. And he was successful. My first encounter with his work was through exactly through one of these folders, handed to me by the cousin of his late wife, Ruth Conrad.

In later years often called the “dean of models,” Theodore Conrad’s outstanding life story warranted his central position within my research beyond purely archival reasoning. He was born on May 19, 1910 in Jersey City, New Jersey, as the son of German immigrants and lived and worked there for most of his life. After studying architecture at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn between 1928 and 1931, he quickly turned to model making as a profession and became one of the first professional and independent architectural model makers in the United States when he opened his own workshop in Jersey City in 1931. Throughout the turmoil of the 1930s’ Great Depression and World War II, the economic boom of the post-war years and the oil crises of the 1970s, Conrad managed to sustain his workshop until his death. He had initially gained wider acclaim when he won first prize at the Delta competition for the best small basement shop in the country in 1934. Early on, he had established important alliances with successful architects based in New York City such as Harvey Wiley Corbett, Wallace Harrison and Philip Goodwin as well as clients such as Nelson Rockefeller. His early commissions as an independent business owner included Rockefeller Center, the Museum of Modern Art and the 1939 New York World’s Fair. After the war-time slump in construction work, Conrad’s career took off fully when he started to work for large International Style offices such as Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and Edward Durell Stone and became the premier model maker in the country engaged in some of the most important and widely publicized building projects.

After three decades in a business he helped invent, in 1962, Conrad was the only model maker to ever receive the AIA Craftsmanship Medal for his lifetime achievement in working with architectural models and his “creative collaboration” in the creation of architecture.

The book

Based on the recent discovery of his fully-preserved private archive-models, photos, letters, business files, and drawings-this book tells the story of Theodore Conrad (1910-1994), the most prominent and prolific architectural model-maker of the 20th century.

Conrad's innovative models were instrumental in the design and realization of many icons of American Modernism-from the Rockefeller Center to Lever House and the Seagram Building. He revolutionized the production of architectural models and became a model-making entrepreneur in his own right. Yet, despite his success and the well-known buildings he helped to create, until now little has been known about Conrad's work and his impact on 20th century architectural history.

With exclusive access to Conrad's archive, as well as that of model photographer Louis Checkman-both of which have lain undiscovered in private storage for decades-this book examines Conrad's work and legacy, accompanied by case studies of his major commissions and full-color photographs of his works. Set against the backdrop of the surge in model-making in the 1950s and 1960s-which Jane Jacobs called “The Miniature Boom”-it explores how Conrad's models prompt broader scholarly questions about the nature of authorship in architecture, the importance of craftsmanship, and about the translation of architectural ideas between different media. The book ultimately presents an alternative history of American modern architecture, highlighting the often-overlooked influence of architectural models and their makers.

What others say about the book:

John Hill on Archidose, November 4, 2021:

“Most interesting to me are the last two chapters. The chapter on photography is fascinating in revealing the technical aspects required last century (pin-hole was preferable to a lens, for instance) and presenting photomontages and other ways in which models were part of the process of image-making. "Model Displays" delves into the increased use and appeal of models in architectural exhibitions, something that remains to this day (I'll admit I gravitate to models rather than drawings if they're included in exhibitions).”

Mark Alan Hewitt on ArchDaily, September 24, 2021:

“There are many fascinating facts, stories, and illustrations in this book, a credit to the author’s research skills and access to the Conrad collection at the Avery Architectural Archives in New York. It appears that much of the text was her dissertation at the University of Zurich, also a credit to her talents. This first large-scale study of an important chapter in the history of modern architecture suggests that much more should be done to explore models as representational types, an important one among an expanding array of media that continues to this day.”

Theodore Conrad with one of his models of Lever House.

Model of Metropolitan Life North Building by Theodore Conrad, ca. 1929.

Theodore Conrad with his model of the Fortune Naval Base, 1940.

Drawing of the base of Collier’s Weekend House.

House model in fall setting, ca. 1940s.

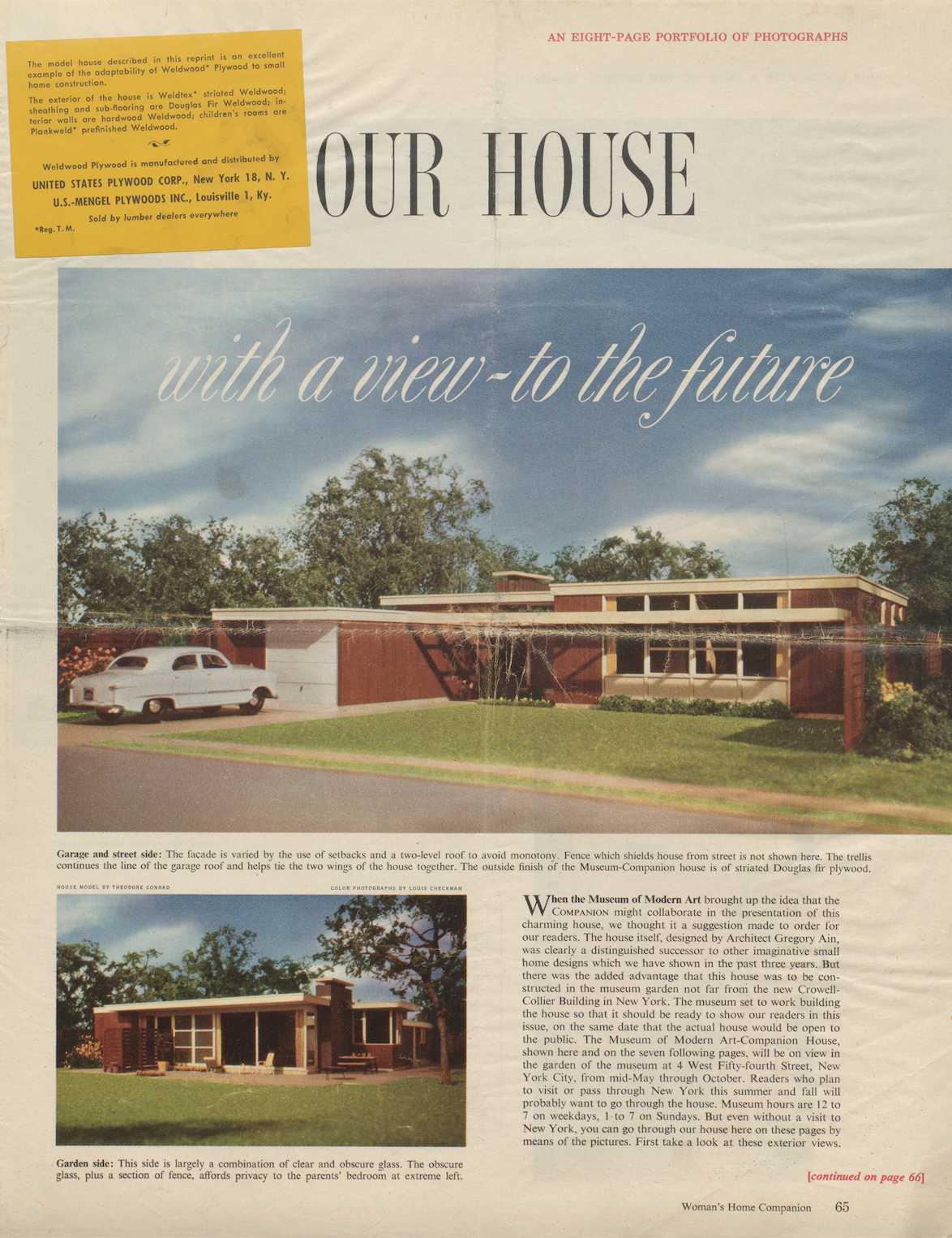

Color model photos in an article in Woman’s Home Companion, 1940s.